The Woman who made a difference in WWII

Virginia Hall: The Most Feared Allied Spy of WWII

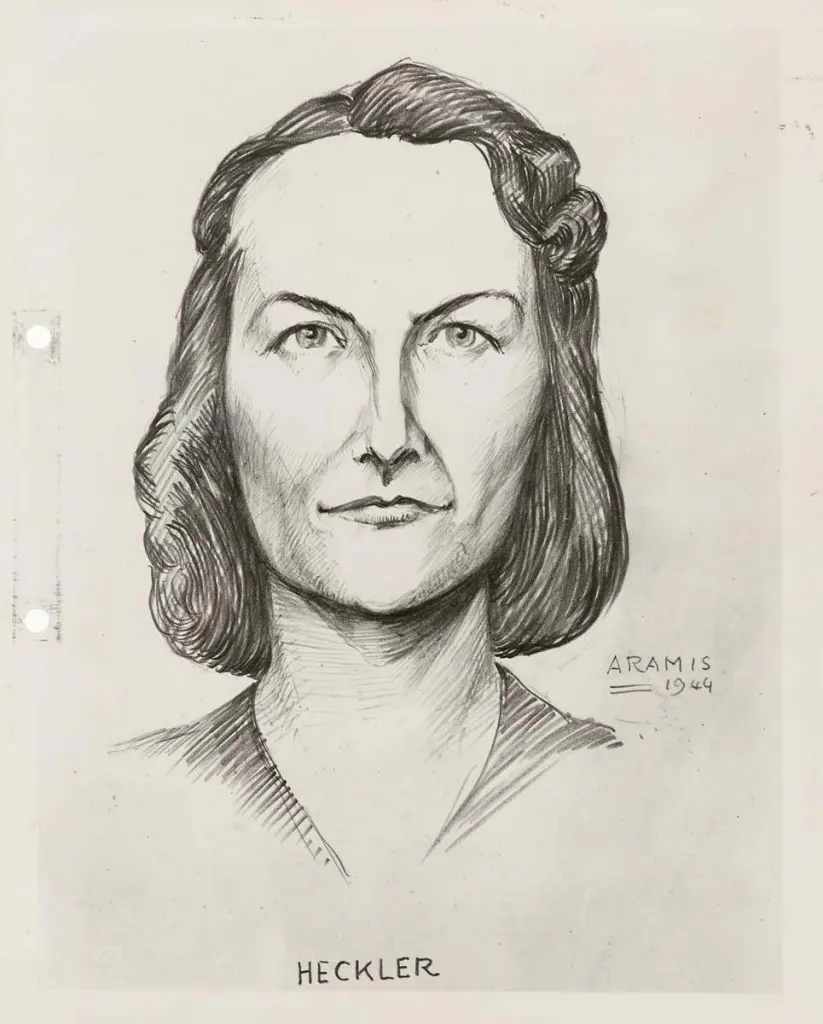

During WWII, Nazi officials were constantly hunting down resistance fighters and the Allied spies who aided them. But there was one foreign operative the Third Reich held special contempt for—a woman responsible for more jailbreaks, sabotage missions, and leaks of Nazi troop movements than any spy in France. Her name was Virginia Hall, but the Nazis knew her only as “the limping lady.”

“I would give anything to get my hands on that limping Canadian bitch,” Klaus Barbie, the infamous Gestapo chief, reportedly grumbled to his henchmen. Despite his cruelest efforts, he never would.

Virginia Hall wasn’t Canadian, but she did walk with a pronounced limp, the result of a freak hunting accident that required the amputation of her left leg below the knee. In its place was a seven-pound wooden prosthetic that she lovingly nicknamed Cuthbert.

Hall was raised in Baltimore, Maryland by a wealthy and worldly family that put no limits on their daughter’s potential. Athletic, sharp, and funny, she was voted “the most original in our class” in her high school yearbook. She began her college studies at Barnard and Radcliffe, but finished them in Paris and Vienna, becoming fluent in French, German, and Italian, with a little Russian on the side.

After graduation, Hall applied to the U.S. Foreign Service, eager to see the world and serve her country, but was shocked to get a rejection letter reading, in effect, “No women, not going to happen,” says Judith Pearson, author of the suspenseful Hall biography The wolves at the door. The true story of America's greatest female spy.

To give up, Hall decided to enter foreign service “through the back door,” says Pearson, by landing a clerk job at the U.S. Embassy in Warsaw, and then at the U.S. Consulate in Smyrna, Turkey. It was during a bird-hunting excursion with American friends in Turkey in 1933 that Hall stumbled climbing over a wire fence and accidentally discharged her shotgun, hopelessly mangling her left foot.

Recuperating back home in Maryland, Hall applied to the Foreign Service again, only to be rejected not because she was a woman, but because she was an amputee.

Hall quit the State Department and went back to Paris as a civilian in 1940 on the eve of the German Invasion. She drove ambulances for the French army and fled to England when France capitulated to the Nazis. At a cocktail party in London, Hall was “railing against Hitler,” says Pearson, when a stranger handed her a business card and said, “If you’re interested in stopping Hitler, come and see me.”

The woman was none other than Vera Atkins, a British spymaster believed to be Ian Fleming’s inspiration for Miss Moneypenny in the James Bond series. Atkins, who recruited agents for Winston Churchill's newly created Special Operations Executive (SOE), was impressed with Hall’s firsthand knowledge of the French countryside, her multi-language fluency, and her unflappable moxie.

In 1941, Hall became the SOE’s first female resident agent in France, with a fake name and forged papers as an American reporter with the New York Post. She quickly proved exceptionally skilled at not only radioing back information on German troop movements and military posts but also at recruiting a network of loyal resistance spies in central France.

The mission of the SOE was to “set Europe ablaze” with guerilla sabotage and subversion tactics against the Nazi forces.

What 1940s spy craft lacked in technological sophistication, it made up in creativity. The BBC would insert coded messages into its nightly news radio broadcasts. Hall would file “news” stories with her editor in New York embedded with coded missives for her SOE bosses in London.

“In Lyon, Hall would put a potted geranium in her window when there was a pickup to be made,” says Pearson, who spoke to some of Hall’s aging compatriots in France. “And the pickup would be a message behind a loose brick in a particular wall, or it might be going to a certain café, and if there’s a message, the bartender would give you a glass with something stuck to the bottom of it.”

Hall became so notorious to Nazi leaders that the Gestapo dubbed her “the most dangerous of all Allied spies.” When Barbie and the Gestapo distributed wanted posters for the “limping lady,” Hall fled the country the only way she could, a grueling 50-mile trek over the Pyrenees mountains southward into Spain. Her Spanish guides first refused to take a woman, let alone an amputee, but she would not be deterred. The November weather was bitter cold and her prosthetic was agonizing.

At a safe house in the mountains, Hall radioed her superiors in London to report that she was OK, but that Cuthbert was giving her trouble. The deadly serious reply from SOE headquarters, which mistook Cuthbert for an informant, read, “If Cuthbert is giving you difficulty, have him eliminated.”

But Hall wasn’t done fighting Nazis. Since the British OES refused to send her back to France as a marked woman, Hall signed up with the U.S. Office of Strategic Service (OSS), a precursor to the CIA.

In 1944, months before the D-day invasion at Normandy, Hall rode a British torpedo ship to France and disguised as a 60-year-old peasant woman, crisscrossed the French countryside organizing sabotage missions against the German army. In one OSS report, Hall’s team was credited with derailing freight trains, blowing up four bridges, killing 150 Nazis and capturing 500 more.

After the war, Hall was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, one of the highest U.S. military honors for bravery in combat. She was the only woman to receive the award during World War II. Back home, she continued to work for the CIA until her mandatory retirement at age 60.

Hall passed away in 1982, and because she eschewed attention and praise, even some of her closest family members didn’t know the full extent of her daring escapades in Vichy France. Pearson says Hall was a spy’s spy to the end.

“I held a memo in my hand from General William Donovan [head of the OSS during World War II] from the 1950s, in which he told Virginia, ‘Okay, you can talk now.’ But she still didn’t,” says Pearson. “That was how Virginia lived.”

Virginia Hall Goillot

Famous memorial VETERAN

BIRTH 6 Apr 1906 Baltimore, Baltimore City, Maryland

DEATH 8 Jul 1982 (aged 76) Rockville, Montgomery County, Maryland.

BURIAL Druid Ridge Cemetery Pikesville, Baltimore County, Maryland.

World War II Spy. She received recognition as an American performing heroic acts for the Allied Armies, first for Britain and then for the United States. She worked for British Special Operations starting in 1941 in Lyon, France. In 1942, the head of the Nazi Gestapo, Klaus Barbie, the "Lyon's Butcher," ordered wanted posters with her face in the hope of capturing "the limping lady." She was considered the most dangerous of all Allied spies. She escaped to Spain, in a three-day journey in heavy snow over the Pyrenees Mountains. As a young lady, she accidentally gave herself a gunshot wound in the foot, which got infected, thus her leg was amputated below the knee. She did this 50-mile journey using a heavy wooden prosthetic leg. While in France, she had a network of 1,500 resistance fighters helping her to destroy bridges or railroads. Her second trip to France was working for the United States for the American Office of Strategic Services. In France from 1944 to 1945, this was even more successful than her first for Britain. She had developed numerous outfits to hide her identity. A make-up artist helped her to change into an elderly crippled lady with bad teeth. She had a dozen alias names. Receiving the Distinguished Service Cross in 1945, she was the most highly decorated female civilian during World War II. In 1943 she was made an honorary Member of the Order of the British Empire and given honors in France also. Her heroic actions were recognized again on the 100th anniversary of her birth date at the British and French Embassies in Washington, D.C. After the war, she worked for the CIA from a desk mainly in the Special Activities Division but helping those behind the Iron Curtain. In 1951, she married OSS agent Paul Goillot, whom she had met during the war in France. The couple continued to work together at the CIA. She was at the CIA for 15 years taking mandatory retirement in 1966, but never spoke publicly of her deeds during the war. Even after her death, her story was confined to the intelligence community. She was the daughter of a well-to-do Baltimore family. After attending Radcliffe College in Cambridge, Massachusetts and Barnard College in New York City, she pursued additional studies in Europe. She had a gift for languages and loved adventure. She became a clerk at the United States Embassy in Warsaw, Poland in hopes that someday she would be a diplomat. Her next assignment was in Ismir Turkey. It was here she had a hunting accident that caused the amputation of her left lower leg. This was followed by an assignment in Venice, Italy, and while in Venice, she learned that her amputation caused her to be rejected from becoming a diplomat, which was her professional goal. At the start of World War II, she was in France and joined the ambulance corps. She traveled from France through Spain to reach England to join the British Special Operations, thus the beginning of her "spy days." Recently, the CIA training hall was named The Virginia Hall Expeditionary Center. A retired CIA officer, Craig Gralley, has written a book about her, "Hall of Mirrors." In 2005, "The Wolves at the Door: The True Story of America's Greatest Female Spy" by Judith Pearson was released. "The Spy with the Wooden Leg: The Story of Virginia Hall" was a biography written by Nancy Polette in 2012. "Woman of No Importance" was written by Sonia Purnell in 2019 with a movie by the same name due to be released the same year. In 2019, she was posthumously inducted into the Maryland Women's Hall of Fame.

Seeking photos and information for the 187th ECB. I will purchase Battalion photos of the 187th Engineer Combat Battalion (H&S, A, B, and C Companies)

Come on people, pitch in, I'm right behind you!

Welcome to the new members of the newsletter. It's always a pleasure to see new people sign up. If you have some information on the battalion, please reach out. No matter how insignificant you may think the information may be, it might lead someone to a new avenue for research.

Contact us at the187thengcobn@aol.com

You can sign up for more information at https://187th-Engineering-Combat-Battalion.ghost.io/ghost/#/site

Note. You can access past postings by clicking on the HOME icon. It will take you to the home page to view past Articles.